About St John's church

There was a church recorded here in Domesday in 1086, although it would have been a small wooden building then. It was endowed with 80 acres of glebe land to support the priest. This is one of the largest areas of land for a Suffolk church apart from the large urban churches. Despite this, Barnby was one of the poorest parishes in the County in the later medieval years — at the time of the Norwich taxation in 1254, Barnby church and its 80 acres of land was taxed at 1 mark (13/4d or 67p). At the same time neighbouring North Cove was taxed at £8, Mutford £10, Ellough £12 and Beccles was taxed at £18/13/4d (£18.67p).

Outside

The core of the building you see today was probably built in the late 12th or early 13th century. The flintwork in the walls is laid in well-defined courses characteristic of this period. The slightly thicker mortar courses between each year’s masonry work, about 12 inches apart, can clearly be seen in the south wall. Along with most parish churches, the chancel was lengthened in the later 13th century. The thinner walls of the eastern end of the chancel are obvious on the inside of the church and evidence of the original apsidal east end can still be seen on the outside — with the beginnings of a rounded end visible beneath the second chancel window on the south wall below the old ground level.

The western end of the nave was extended after the chancel extension, but before the tower was built. This can be seen the lack of coursing and the extensive use of rough early medieval brick, including the quoins. Bricks of this age and roughness are most likely to have been imported from the Low Countries, sometimes as ballast on return journeys exporting wool. They are far too rough to have been reused Roman items. Apart from one or two repairs and a couple of putlog holes (where the medieval scaffolding was passed through the walls) there are no bricks at all in the earlier central part of the church.

The original very simple north and south doors can also be seen in the walls to the east of the current entrances. The blocked north door, just to the east of the porch, still retains its original oak lintel at the door head, rather than the usual arch. The south door, some two metres to the east of the large blocked door still has the scratch dial in its eastern jamb.

The tower is another 50 years or so younger, firmly in the Decorated period — probably built not long before the Black Death in 1349, and the only part of the church to employ the more expensive freestone (but in very small blocks).

The porch seems to have been added in the fifteenth century, unusually on the north door, perhaps indicating that by then most of the village was to the north of the church. The outer porch doorway is a fine example of a durn door, where the arch is formed by shaped jambs and the head of the arch is cut into the lintel.

Little “improvement” has taken place over the centuries, so many of the original building features remain, such as the flint quoins (corners) to the chancel, and the medieval bricks making the nave quoins. Only the later tower has used the more expensive dressed stone, and even then only using very small stones. The remains of a scratch-dial (a “sun dial” to tell worshippers the times of services) can be seen in the middle of the south wall. It was located on the eastern jamb of the original doorway before the nave was extended. Unusually, it has been cut in a piece of soft field-stone, rather than in the more usual material of dressed limestone, presumably because none was available. Faint division marks can still be seen at the bottom of the “dial”.

The later south door has also been blocked for centuries. It has always been assumed that this happened after the part of the village to the south of the church disappeared. In 1999, members of the Local History Group discovered evidence of two house sites in the field to the south-east, with pottery and metal finds that indicate that the sites were occupied between the 13th and 18th centuries. Since then, all the land round the church has been used as farmland.

The priest’s door on the north side of the chancel is shown as already being blocked in an engraving of the 1840s.

Restoration work on the drainage around the walls during the 1980s discovered burials older than the west end of the nave in the wall trench, and also the remnants of the path to the original south door, almost 2 feet below the current ground level.

Inside

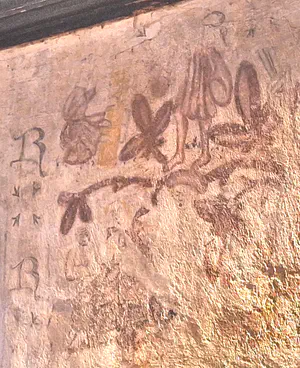

Possibly unique in Britain is the medieval door to the banner stave locker which is still in place to the west of the south door (for storing the banners used in medieval processions). It is elaborately decorated with rudimentary scratches and piercings and is thought to be unfinished. There are other lockers in existence, mainly in north-east Suffolk, but none still has its door intact.

Adjacent to it are the remains of the stoup for washing hands, showing that the south entrance was originally the main one. There are faded remains of the 15th-century wall paintings, depicting the crucifixion and the seven corporal works of mercy, with St Christopher (the Patron Saint of travellers) on the south wall, opposite the north entrance, showing that by the 15th century, the north entrance was the principal one.

The font is made of Purbeck “marble” and is probably 13thcentury, with the blind arches on the bowl and separate pillars common in the Early-English Gothic style, the base is modern. The rood screen has been removed completely, part of which has been rehung towards the west end. There appears never to have been a stair to the rood beam, perhaps just a ladder. In the chancel, the piscina has been built into the east wall, rather than the usual position in the south wall, with a strange-shaped arch above it. The clergy “sedilia” for resting during the long services consists only of a built-up stone block.

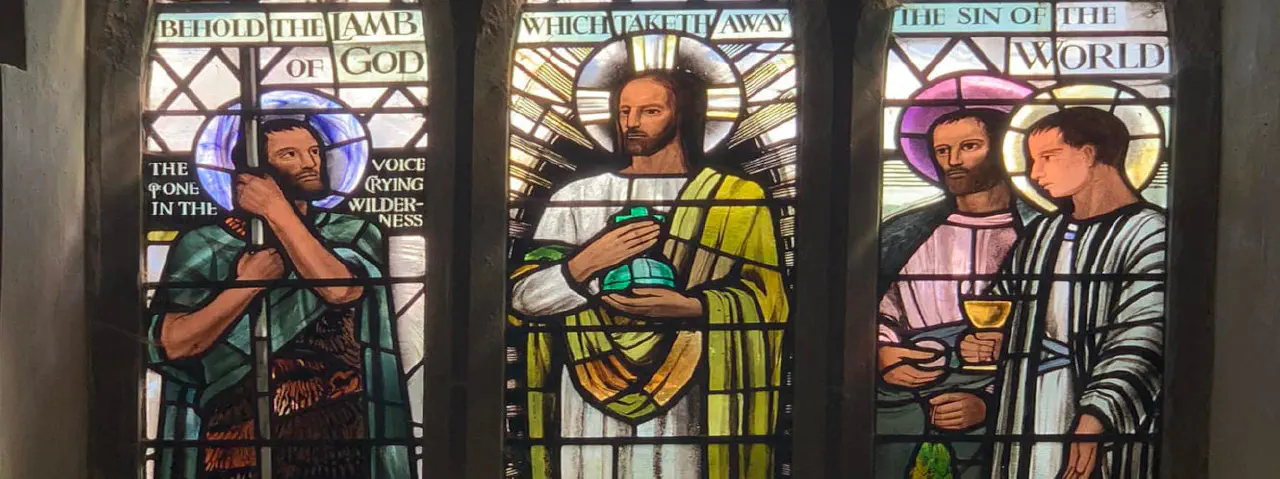

The altar retains the original stone mensa slab, complete with the five consecration crosses; and the furniture is completed by the fine 15th century oak lectern in the form of a carved eagle. The chancel east window, showing John the Baptist on the left, is one of the last commissions by Margaret Aldrich Rope from Leiston. Dedicated in 1953, it is one of two Rope-designed windows in the church, the other is the Second-World-War Memorial to the two Barnby men killed in the war.

Ian Hinton - Norfolk Historic Buildings Group